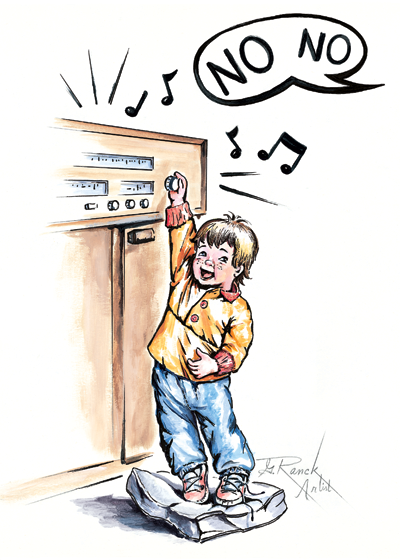

Children under the age of three do not understand "no" in the way most parents think they do. (And, a full understanding of "no" doesn't occur magically when the child turns three. It is a developmental process.) "No" is an abstract concept that is in direct opposition to the developmental need of young children to explore their world and to develop their sense of autonomy and initiative, as discussed in Chapters 4 and 5 of Positive Discipline for Preschoolers.

Oh, your child may "know" you don't want her to do something. She may even know she will get an angry reaction from you if she does it. However, she cannot understand why in the way an adult thinks she can. Why else would a child look at you before doing what she "knows" she shouldn't do, grin, and do it anyway?

Around the age of one, children enter the "me do it" stage. This is when they develop a sense of autonomy vs. doubt and shame. Two through six heralds the development of a sense of initiative vs. guilt. This means it is their developmental job to explore and experiment. Can you imagine how confusing it is to children to be punished for what they are developmentally programmed to do? They are faced with a real dilemma (at a subconscious level). "Do I obey my parent or my biological drive to develop autonomy and initiative by exploring and experimenting in my world?"

These stages of development do not mean children should be allowed to do anything they want. It does explain why all methods to gain cooperation should be kind and firm at the same time instead of controlling and/or punitive. This is a time of life when your child's personality is being formed, and you want your child to make decisions about him or herself that say, "I am competent. I can try and make mistakes and learn. I am loved. I am a good person." If you are tempted to help your child learn by guilt and shame and punishment, you will be creating a discouraging situation that is difficult to reverse in adulthood.

To help a toddler develop autonomy instead of doubt and shame, and to help a two- to seven-year-old develop initiative instead of guilt, try some of the following methods that invite cooperation:

- If you are screaming, yelling, or lecturing, stop. All of these methods are disrespectful and encourage doubt, shame, and guilt in the future.

- Instead of telling your child what to do, find ways to involve him/her in the decision so he/she gets a sense of personal power and autonomy. "What are we supposed to do next?" (For pre-verbal children say, "Next, we _____," while kindly and firmly showing them instead of telling them.)

- Be respectful when you make requests. Don't expect children to do something "right now" when you are interrupting something they are doing. Ask, "Will it work for you to do this in five minutes or in ten minutes?" Even if you don't think a younger child understands completely what you are saying, you are training yourself to be respectful to the child by giving choices instead of commands. Another possibility is to give him/her some warning. "We need to leave in a minute. What is the last thing you want to do on the jungle gym?"

- Carry a small timer around with you. Let your child help you set it to one or two minutes. Then let him/her put the timer in his/her pocket so he/she can be ready to go when the timer goes off.

- Give him/her a choice that requires his/her help. "It will be time to go when I count to 20. Do you want to carry my purse to the car, or do you want to carry the keys and help me start the car?" "What is the first thing we should do when we get home, put the groceries away, or read a story?"

- Pre-verbal children might need plain ol' supervision, distraction, and redirection. In other words, as Dreikurs used to say, "Shut your mouth, and act." Quietly take your child by the hand and lead him/her to where he/she needs to go. Show him/her what he/she can do instead of what he/she can't do.

- Use your sense of humor: here comes the tickle monster to get children who don't listen.

- Be empathetic when your child cries (or has a temper tantrum) out of frustration with his/her lack of abilities. Empathy does not mean rescuing. It does mean understanding. Give your child a hug and say, "You're really upset right now. I know you want to stay, but it's time to leave." Then hold your child and let the child cry and have his/her feelings before you move on to the next activity.

- Children usually sense when you mean it and when you don't. Don't say anything unless you mean it and can say it respectfully. Then follow through with dignity and respect--and usually without words. Again, this means redirecting or "showing" them what they can do instead of punishing them for what they can't do.

- Create routines for every event that happens over and over: morning, bedtime, dinner, shopping, etc. Then ask your child, "What do we need to do next on our routine chart?" For children who are younger, say, "Now it's time for us to _____."

- Understand that you may need to teach your child many things over and over before he/she is developmentally ready to understand. Be patient. Minimize your words and maximize your actions. Don't take your child's behavior personally and think your child is mad at you or bad or defiant. Remain the adult in the situation and do what needs to be done without guilt and shame.

- Understand that your attitude determines whether or not you will create a battle ground or a kind and firm atmosphere for your child to explore and develop within appropriate boundaries.

Your job at this age is to think of yourself as a coach and help your child succeed and learn how to do things. You're also an observer, working on learning who your child is as a unique human being. Never underestimate the ability of a young child, but on the other hand, watch carefully as you introduce new opportunities and activities and see what your child is interested in, what your child can do, and what your child needs help learning from you.

Safety is a big issue at this age, and your job is to keep your child safe without letting your fears discourage him/her. For this reason, supervision is an important parenting tool, along with kindness and firmness while redirecting or teaching your child. For example, parents can "teach" a two-year-old child not to run into the street, but still would not let him/her play near a busy street unsupervised because they know they can't expect him/her to "understand" what he/she has learned well enough to have that responsibility. So why is it these same parents expect their children to "understand" when they say, "No!"

Mrs. Foster was wondering why she ever got into the parenting business. It felt to her that both she and her child were out of control. She did not like it that he would not "mind her," and she did not like it that she was yelling and using punitive methods that didn't work.

She attended a parenting class for parents of preschoolers and learned about age-appropriate behavior. When she changed her expectations about the "perfect child who obeyed her every command," she began to enjoy her child's experimentation with autonomy and initiative. Instead of trying to control him, she started guiding him away from inappropriate behavior by showing him what he could do.

She was most amazed at how much her child seemed to calm down when she calmed down. Frustrating episodes occurred less often and were solved more quickly because of her new understanding.

When you understand that children don't really understand "no" the way you think they should, it makes more sense to use distraction, redirection, or any of the respectful Positive Discipline Methods.

Activity

The following demonstrations illustrate intellectual development, and help parents understand why children can't understand some concepts (such as no) as soon as they think they can.

- Take two balls of clay that are the same size. Ask a three year old if they are the same. Make adjustments by taking clay from one ball and adding it to the other until the child agrees that they are the same size. Then, right in front of him/her, smash one ball of clay. Then ask him/her if they are still the same. He/she will say "no" and will tell you which one he/she thinks is bigger. A five year old will tell you they are the same and can tell you why.

- Find two glasses that are the same size, one glass that is taller and thinner, and one glass that is shorter and fatter. Fill the two glasses that are the same size with water until a three-year-old agrees they are the same. Then, right in front of him/her, pour the water from one of these glasses into the short, fat glass, and the other one into the tall, thin glass. Then ask him/her if they are still the same. Again, he/she will say "no" and will tell you which glass he/she thinks has the most. A five year old will tell you they are the same and can tell you why.

A typical child on Piaget's conservation tasks